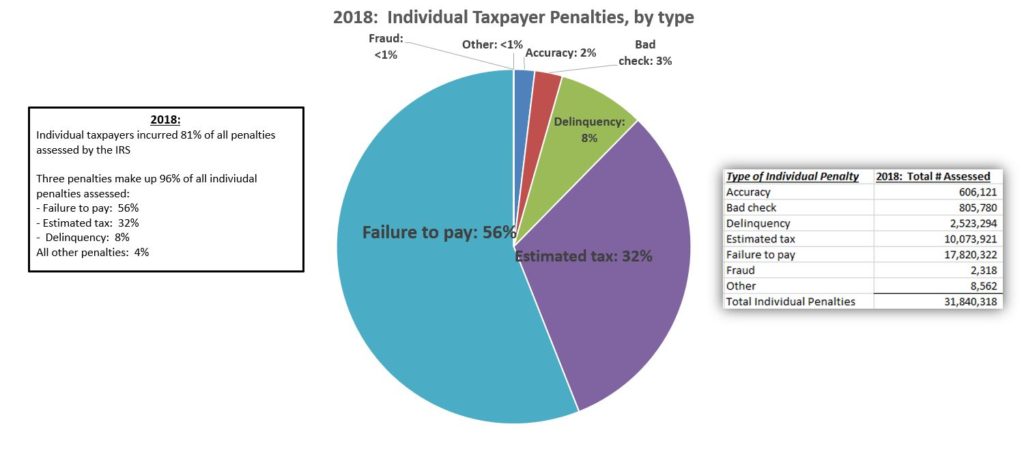

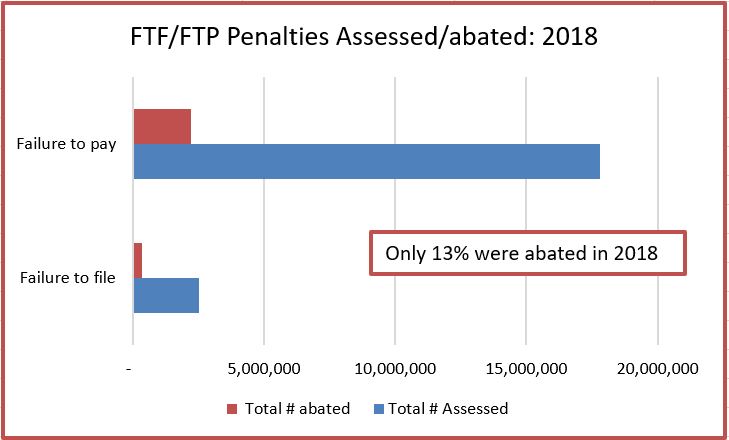

In 2018, the IRS assessed over 20 million failure to file (FTF) and failure to pay (FTP) penalties to individuals. The FTF and FTP penalty make up almost 2/3rds of all penalties assessed and they are the frequent subject of the most penalty abatement requests.

The problem: abatement is usually not requested or is denied by the IRS. Only 13% of the FTF and FTP penalties were abated in 2018.

Requesting penalty abatement

A request for penalty abatement requires the taxpayer to ask the IRS to remove the penalty after the penalty is assessed. To qualify for relief, the taxpayer must meet one of the five reasons for penalty abatement. Three forms of relief: disaster relief, relief provided by a specific law, and audit penalty relief in IRS appeals, are not common. Also, the three relief provisions are likely to be provided automatically, or in the case of the audit, in IRS appeals. For example, taxpayers who file late due to a natural disaster are automatically provided penalty relief (for a certain period of time) if they are located in a zip code for the presidentially-declared disaster area.

Most penalty abatement requests are for first-time abatement and for reasonable cause. First-time abatement (FTA) provides relief for the FTF and FTP penalties for taxpayers with a clean compliance record (generally, taxpayers who do not have any penalties in the prior three years). If a taxpayer requests penalty relief for the FTF or FTP penalty, the IRS first looks to see if they qualify for FTA relief. If the qualify, the relief is applied, without regard to any reasonable cause argument.

If FTA does not apply, the taxpayer is usually looking for “reasonable cause” abatement. Reasonable cause requires that the taxpayer acted in good faith, but for circumstances outside of their control (the “reasonable cause”) were not able to comply. For example, a taxpayer is likely to have reasonable cause for late filing if they missed their October 15th filing deadline because they were suddenly hospitalized on October 13-19th and late filed on October 21st. In this example, the taxpayer would argue that their circumstances outside of their control (illness or injury) caused the noncompliance. Other factors would weigh in also, such as the time it took to comply after the circumstances as well as the taxpayer’s history of compliance.

How could the IRS deny my penalty abatement request?

Many taxpayers who have more than sufficient penalty abatement reasonable cause arguments and supporting circumstances have their abatement requests denied. Why? The answer lies in the IRS computerized penalty abatement decision tool – called the “Reasonable Cause Assistant” or “RCA.” The RCA is used by IRS personnel to make uniform penalty abatement decisions. Unfortunately, the uniform decision appears to be to be a consistent “denied abatement.”

The National Taxpayer Advocate first brought up her concerns with this tool in the 2010 Report to Congress. Over-reliance on the harsh RCA was listed as one of the most serious problems at the IRS. In 2019, it appears that the situation has not improved.

Here’s the problem with the RCA: rather than look at the totality of the taxpayer’s circumstances or ask more questions of the taxpayer, the RCA looks at each reasonable cause argument to see if that one argument meets a bright-line programmed threshold for abatement. If each argument, on its own merits, does not meet the RCA’s programmed threshold or the IRS has more questions, the entire abatement request is denied. The IRS does not look to all of the other factors or request the taxpayer to further explain their circumstances. In rare circumstances (usually where the taxpayer has only one cause argument), the RCA tool may request more information from the taxpayer.

The RCA process

During the penalty abatement review, the IRS representative will complete the RCA by interpreting which factors are present based on the request letter (or Form 843) submitted. The RCA tool will either conclude “deny” or ask additional questions for each reasonable cause factor. The questions may or may not be addressed by the taxpayer in the details of the letter. Rather than deciding the evidence weighs in favor for the taxpayer, the IRS appears to summarily rule that the threshold for abatement has not been met. Ultimately, the taxpayer receives a denial letter that seems to focus on one small part of the entire letter. The taxpayer is confused by the IRS’ answer and becomes suspicious of the process and the competence of the decision maker.

Here is a real-life example: a taxpayer files and pays late because they were incapacitated due to a car accident. They argue their serious medical condition and resulting aftermath of hardships as reasonable cause for not filing and paying on time for three consecutive years: 2014-2016. The taxpayer provides a statement and a doctor’s note that they were in the hospital for several months, out of work for three years, and had hundreds of medical visits. The taxpayer even provides hundreds of bills for inpatient and outpatient services over the three-year period. However, the IRS wants information about other activity. For example, the IRS observes a small amount of W-2 income for 2016 and wants to know how the taxpayer could work and not file their tax return. The IRS also wants to know specific dates that they were incapacitated, including specific answers on whether they could perform other actions. They also want to know whether a guardian was appointed during their period of being incapacitated. The taxpayer also stated in their request that they were financially strapped during that time – causing additional hardship. In this case, the IRS homed in on the “financial hardship” as not being reasonable cause for filing late – ignoring the accident and serious long-term medical condition that left the taxpayer hospitalized and unable to carry on their affairs for almost two years. The taxpayer is confused because they provided the financial hardship as another hardship factor, mainly to explain as a reason for paying late- not filing late. The taxpayer receives a complete denial letter with the confusing explanation that financial hardship is not a reason for filing late. The letter mentions nothing about the failure to pay abatement request. In the end, the taxpayer is baffled, and questions the integrity of the tax system and the IRS.

What can you do?

Penalty abatement requests, other than for FTA, appear to have a grim chance of success for taxpayers. Besides having a good reasonable cause argument, there are some simple tips that you can use that will greatly increase your likelihood for abatement:

- Be prepared to appeal the denial – want a human to see the big picture? Ask for an appeal of the IRS’ determination. Most tax professionals know it is par for the course to request a full review by a person (an IRS appeals officer) who can apply the facts and circumstances with the law -and ignore the RCA.

- Do not group years in abatement requests – if the taxpayer is asking for abatement of penalties for multiple years, it is best to separate each year into a separate request. This makes it easier for the IRS to isolate whether each year qualifies for reasonable cause. It also makes it easier for the taxpayer to argue. Also, if the facts are similar in each year, any IRS approval of one year can be used in arguing the abatement for another year.

- Avoid the hot button denials for failure to file – for failure to file, do not list financial hardship or reliance on a tax pro as cause for late filing. Trust me- these arguments lead to absolute denials, even in IRS appeals.

- Don’t pay the penalty until your case is heard in appeals – I once heard an IRS official at an IRS Tax Forum conference state: “if I wanted to contest a penalty, I would never pay it first.” Why? Because paying the penalty will remove the possibility of an important appeals option: the Collection Due Process hearing (“CDP”). This hearing is more serious than an informal IRS penalty abatement appeals hearing. CDP hearings are more formal and require the appeals officer to prepare a written determination letter of the findings. The CDP determination can be appealed to the Tax Court, whereas the informal hearing is final after the decision.

- Be prepared to show that you are a compliant taxpayer – first instances of non-compliance (even though you don’t qualify for FTA), voluntary compliance actions (i.e. the IRS did not force you to comply), and future compliance go a long way with the IRS. The purpose of penalties is to deter non-compliance. If you are compliant, you can argue this is an isolated incident, outside of your control, that caused the noncompliance.

- Be prepared to show how other aspects of your life were influenced by the circumstances outside of your control – the reasonable cause circumstances cannot just affect your tax obligations, it must affect other areas of your life.

The bottom line

To argue your case, it is best to be prepared to appeal. Appealing your case will offer you the opportunity to lay out your facts and argument, and interact with a person at the IRS who is not using the RCA to make a facts and circumstances decision.